The Islamic State’s Shadow Governance in Eastern Syria Since the Fall of Baghuz

Original article published on Combating Terrorism Center by Aaron Y. Zelin and Devorah Margolin on 9 September 2023.

Abstract: Since losing its last semblance of control in Syria in March 2019, the Islamic State has spent the last four and a half years not only attempting to survive, but also working to create the conditions for returning to territorial control. While it is true that the organization’s insurgency has been degraded in recent years, only focusing on the Islamic State’s attack claims and propaganda misses an important trend happening at the local level: Despite the best efforts of the Global Coalition Against the Islamic State and the Syrian Democratic Forces, the Islamic State has continued attempts to govern as shadow actors in eastern Syria. The Islamic State’s shadow governance efforts can be seen occurring on four main axes: taxes, moral policing, administrative documents, and retaking of territory (albeit for brief periods of time). The Islamic State’s level of governance today is nowhere near where it was when it controlled territory the size of Britain from 2014-2017. Yet, these governance attempts illustrate that the group may be stronger than many assume, while also highlighting that the group’s interest in governing and controlling territory has not waned in recent years.

Since the Islamic State lost its last bit of physical territory in Baghuz al-Fawqani, Syria, in March 2019, much focus has unsurprisingly been placed on the group’s terrorism and insurgency campaign to try to retake territory, as well as the indefinite detention of approximately 60,000 Islamic State-affiliated individuals in northeast Syria.a Yet, quietly, within a few short months of the group’s territorial collapse, there were already signs that it had not given up its governance ambitions and was still attempting to enforce its writ in territories it once held. As early as June 2019, evidence of the Islamic State’s governance attempts appeared in Deir ez-Zor Province (formerly the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Khayr) and Hasakah Province (formerly the group’s Wilayat al-Barakah).

Although the Islamic State has yet to regain permanent tamkin (consolidated administrative control)1 over any area in eastern Syria, through its shadow governance activities over the past four years, the group has continued to project power and instill fear into local populations across eastern Syria. In doing so, the Islamic State seeks to create a mechanism to reimplement its caliphate project quickly if it were ever able to occupy territory again in the future. More immediately, however, these efforts by the Islamic State provide financial infrastructure for the organization to continue its terrorism and insurgency campaign, primarily directed against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), including SDF-run detention centers and prisons holding Islamic State-affiliated individuals. For example, on July 31, 2023, Internal Security Forces in northeast Syria (supported by coalition forces) arrested an Islamic State-affiliated leader accused of conducting finance operations in Deir ez-Zor.2

Therefore, while it is important to continue to track the Islamic State’s claimed attacks and ongoing insurgency, doing so without understanding evolving dynamics at the local environment misses the broader aperture of Islamic State activity. In order to understand the full nature of the Islamic State threat today in Syria, one must look below easily quantifiable actions at what the group could be hiding, specifically indicators that can evaluate its strength below the surface. This is in part because over the past few years, a lot of the Islamic State’s governance activity has occurred at night or in areas where the SDF has reduced operations due to security concerns for its own safety. To address this gap in understanding the current status of the Islamic State, this article will explore the group’s history of governance and analyze the reality of the Islamic State’s propaganda and claims of responsibility for attacks since the fall of its territorial control, before examining its shadow governance efforts in eastern Syria between 2019 and 2023.

The Islamic State’s History of Governance

The Islamic State movement’s long history can be broken into several distinct periods.3 The group’s foundation in the 1990s until 2006 was defined by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s leadership. This saw the group move from the training camps of Afghanistan to Iraq where, under the name Jama’at al-Tawhid wa-l-Jihad and later al-Qa`ida in the Land of Two Rivers (better known as al-Qa`ida in Iraq, or AQI), it rose to notoriety for waging a bloody sectarian insurgency.

In October 2006, the group’s next phase began. Then-leader of AQI, Abu Ayyub al-Masri (Abu Hamza al-Muhajir), pledged allegiance to the new self-declared leader of the faithful, Abu Umar al-Baghdadi, and with it established its first self-declared state, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). In January 2007, ISI’s Shaykh ‘Uthman ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Tamimi released a book explaining the group’s rationale for declaring its state.4 In his writing, al-Tamimi outlined ISI’s responsibilities as a state in the areas it governs: “prosecuting criminals and sinners, implementation of the hudud (fixed punishments in the Qur’an and Hadith), mediating and resolving conflicts, providing security, distributing food and relief, and selling oil and gas.”5

Although ISI proclaimed itself as a state,6 the Islamic State of Iraq controlled limited territory, for insubstantial amounts of time—due to the U.S. military occupation, but also as a consequence of rival insurgent and tribal competition for power. ISI attempted to show a “veneer of legitimacy” by establishing a cabinet of ministries first in April 2007 and again in September 2009. Nevertheless, because of numerous obstacles facing ISI, the group was unable to properly implement the administrative responsibilities al-Tamimi outlined.7 Instead, ISI primarily focused on “instituting hisba (moral policing) activities and targeting enemies as murtadin (apostates) who were seen as legitimate to target and kill.”8 This period helped to set up the Islamic State’s later governance, which was marshaled by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi after he became the leader in 2010 when al-Muhajir and Abu Umar were killed.

The Islamic State movement’s next period spanned 2012 to 2017 and marked its transnational expansion. Renamed in April 2013 to the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (aka ISIL, the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant), ISIL’s main focus was to present itself in a positive light to the Syrian population through da’wa (missionary) forums and by providing services,9 prior to a wave of infighting that began in January 2014 between ISIL and revolutionary, Islamist, and other jihadi factions in Syria.10 As ISIL, the group also carried out “softer” moral policing, including burning cigarettes and confiscating alcohol.

Yet, like a decade prior, ISIL killed other leaders from rival Syrian insurgent groups, prompting backlash. Due to infighting, ISIL was pushed out of Latakia, Idlib, and parts of Aleppo between January and March 2014.11 As a result, the organization focused its state-building project in eastern Syria in Raqqa governorate and parts of Deir ez-Zor governorate. After ISIL’s consolidation in the east, reports of “harsher punishments began to appear, such as cutting off hands for robbery or crucifying alleged apostates.”12 As ISIL, the group “sought to appear as a state-like entity, showing off its various administrative departments including its da’wa offices, shariah courts, religious schools, police stations, and local municipalities, among others.”13 Despite these efforts, during this period the group performed “an uneven governance strategy across its proto-wilayat (provinces).”14

In June 2014, the group captured Mosul and declared its caliphate, changing its name again—to simply the Islamic State. During this time, the Islamic State took control of large swaths of territory across Syria and Iraq, and created an intricate bureaucratic system that sought to touch on and govern all aspects of the lives of those that lived under its control.15 When compared with its first state as ISI and its building toward a second state as ISIL, the post-June 2014 Islamic State governance structures, plans, and implementation were far superior.

At its height, the Islamic State operated government dawawin (administrations; diwan as singular) across numerous provinces.16 These included: Administration of the Judiciary and Grievances, Administration of the Hisba (Morality Police), Administration of Da’wa (Proselytization) and Mosques, Administration of Zakat and Charities, Administration of the Soldiers, Administration of Public Security, Administration of the Treasury (Finance), Administration of Media, Administration of Education, Administration of Health, Administration of Agriculture and Livestock, Administration of (Natural) Resources, Administration of Services (Water, Electricity), Administration of Spoils of War, and Administration of Real Estate and Land Tax. It used these government bodies to regulate social relationships, extract resources from local populations, and appropriate those resources for their own gain.17 But also during this period, the Islamic State constantly struggled to balance its ideology with the practical realities of its state-building project.

From 2017 to today, the Islamic State has been characterized by decline. Leading up to the full loss of territory in March 2019, the Islamic State took active measures to consolidate its organizational structure and to position itself to survive as an underground insurgent group. Unlike previously when it had a series of wilayat (provinces) within a particular country, the group melded them together into one “province” to streamline decision-making and operations. In the case of Syria, this transformed Wilayat al-Raqqah, Wilayat Halab, Wilayat al-Barakah, Wilayat al-Khayr, Wilayat al-Furat, Wilayat Homs, Wilayat Hamah, Wilayat Dimashq, Wilayat Hawran to just Wilayat al-Sham in mid-July 2018.b However, it is important to acknowledge that despite the fact that the Islamic State has been on the defensive, it retains its governance ambitions.

Do Numbers Tell the Whole Story? The Current State of Islamic State Propaganda and Claimed Attacks

Since 2019, the Islamic State has been relatively quiet on the propaganda front when it comes to eastern Syria. Most of the limited focus has been on the so-called daily life in the caliphate. But, without the physical territory it once held, today it usually features fighters hanging around one another, praying, cooking, or preparing for a battle during Ramadan or Eid al-Adha.

From mid-2019 to mid-2020, the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Sham (in its former provinces of al-Khayr and al-Barakah) media office in Syria released three videos threatening its various enemies (SDF, coalition, local leaders, and activists) in northeast and eastern Syria.18 This was accompanied by an Al Naba—the Islamic State’s weekly newsletter—interview in mid-November 2020 with Islamic State commander Abu Mansur al-Ansari in which he stated how terrible life had become under SDF rule in the area and that the Islamic State would continue to fight for people locally against this so-called “apostate” force.19 More recently, an Al Naba editorial in late January 2022, praised Islamic State fighters for the prison break attack earlier that month at Ghwayran.20

Since 2019, the majority of Islamic State propaganda from eastern Syria has focused on daily life and the group’s enemies. In 2022, a unique piece of video propaganda was published showing Islamic State fighters in eastern Syria praising the efforts of their counterparts in the Islamic State’s self-proclaimed provinces in West Africa, the Sahel, and Central Africa.21 In doing so, the Islamic State was able to contextualize the group’s more successful operations in other areas around the world.

When zooming out to examine the rest of Syria, the Islamic State’s weekly newsletter Al Naba has continued to feature polemics against enemies outside of its core forces in eastern Syria.22 Since the fall of Baghuz, the Islamic State has verbally gone after the jihadi group that controls northwest Syria, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, nine times, the Assad regime four times, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army twice, and Russian forces once.23

Several successful counter-operations against the Islamic State have resulted in the death of four leaders since October 2019, including Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, and very recently Abu al-Husayn al-Husayni al-Qurashi. Islamic State propaganda has featured several new bayat (religious oaths of allegiance) taken by fighters in the region following the ascension of each new leader.24 When examining the current state of Islamic State propaganda, the group has had more overall losses than wins. That being said, it has continued its calls to break its supporters free from prisons and detention camps.25 In many ways, the Islamic State hopes to wait out its strongest enemy: the United States. If Washington were to withdraw U.S. forces from northeastern Syria, this would not only animate the Islamic State’s propaganda, but also provide the space for the group to up the tempo of its now lagging operations.

When looking closer at the group’s insurgency, the Global Coalition Against the Islamic State has seen many successes in the fight against the group since 2019. Successful counter-financing operations coupled with leadership attrition have significantly degraded the group. The military operations against the Islamic State have been led by the Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR)—stood up by U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM)—which found in 2023 that “ISIS capabilities remained ‘degraded’ due to Coalition-assisted counterterrorism pressure, but the group continued to pose a threat.”26

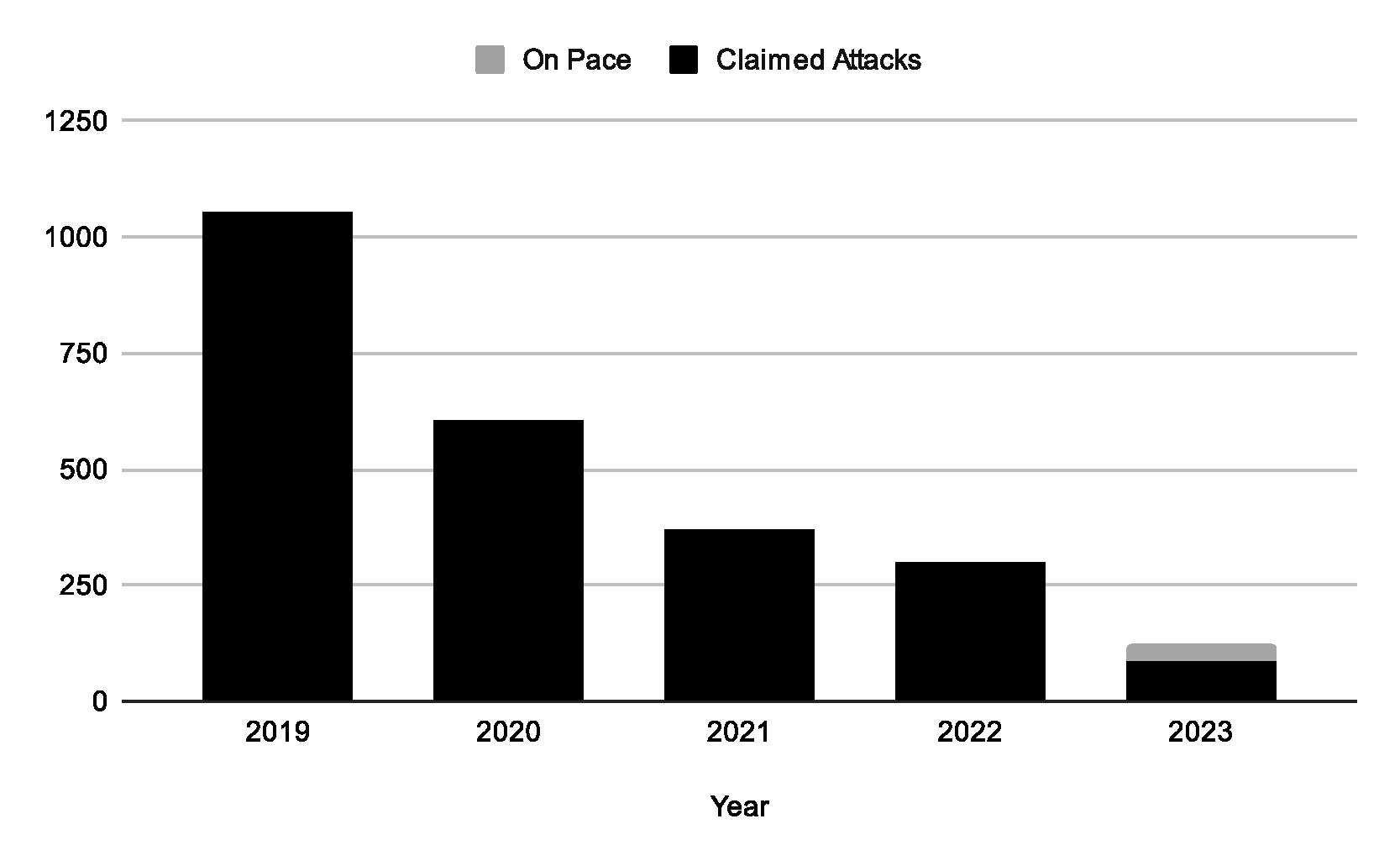

This finding by CJTF-OIR seemingly corresponds with quantifiable statistics on the ground. Over the past four years, the number of claimed attacks by the Islamic State in Syria has gone down significantly every year; it dropped from 1,055 in 2019, to 608 in 2020, to 368 in 2021, to 297 in 2022. Thus far, in 2023, the Islamic State has claimed only 90 attacks in Syria as of September 19. This means that the Islamic State is on pace for 125 attacks in Syria in 2023, the lowest number of claimed operations to date.

Despite these impressive statistics highlighting counter-operations against the Islamic State, researchers such as Aymenn Al-Tamimi, Haid Haid, Gregory Waters, and Charlie Winter have identified that the Islamic State has been underreporting its claimed attacks in different parts of Syria, including the “badiyah” Homs desert region and in the Hawran in southern Syria.27 These scholars highlight that this is due to two possible reasons, either a concerted effort to underreport these attacks, or that Islamic State propagandists have been unaware of the full scope of the group’s ground operations due to communication issues.

According to a series of leaked internal Islamic State documents originating from the fall of 2020,28 this has also been the case in eastern Syria in the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Khayr alongside Homs and the Hawran. According to these internal documents, the rationale for underreporting the number of attacks appears to be twofold in all three territories: first, worries over greater enemy action (the Assad regime and the anti-regime rebel insurgents) against the Islamic State if it publicizes the attacks it has conducted; and second, a lack of communication and media equipment to record or share information (audio/visual) from the attacks to the Central Media Diwan. In one of the letters, a media emir named Saqr Abu Tayim stated that some cells in Wilayat al-Khayr, for example, only have “one mobile device” and do not receive enough funding “to subscribe to the Internet.”29

While those two factors are relevant, there is also another that came up within these three territories in the leaked internal Islamic State documents and seems to be most pertinent to this discussion: Namely, there is a rift between the media and military officials within the Islamic State’s operations. Military officials overruled the group’s media officials due to security concerns or not seeming to think claiming everything is always important.30 The documents also alleged that Islamic State military officials sometimes remove details from reports on claimed operations in order to downplay the extent of attacks. The documents further contended that this “suppression policy” is not always used consistently, as military officials are sometimes okay with reporting on an attack in one area one day, but refuse to grant approval the next day.31 The indications of under-reporting of attacks by the Islamic State discussed above and further discussed immediately below suggest that although these Islamic State documents are nearly three years old now, these trends and rifts remain consistent.

One way of digging deeper on the degree to which the Islamic State may be underreporting attacks is to examine data reported by the Rojava Information Center (RIC) on Islamic State sleeper cell attacks in SDF-controlled areas since the fall of the Islamic State’s territorial control. Similar to the data on Islamic State-claimed attacks, this RIC data should also be caveated, as the RIC is closely aligned with the SDF, who have their own interests in the current situation. Moreover, when looking at the data side by side, it is important to acknowledge that the Islamic State’s claimed numbers are for all of Syria, while RIC’s are only for the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), the Kurdish civil government operating in the northeast region of the country.

With that said, RIC data also confirms that there has also been a drop in Islamic State attacks over the years: from 906 attacks in 2019, to 572 attacks in 2020, to 274 attacks in 2021, and a small spike with 285 attacks in 2022.32 Thus far in 2023, the RIC has recorded 139 Islamic State attacks through August, which equates to being on track for 208 attacks by end of year.33 Therefore, while there has been a drop since 2021, Islamic State attacks logged by the RIC in eastern Syria have remained relatively stagnant and have seemingly not decreased as the rate suggested by the Islamic State’s Syria-wide claims. This data gives further credibility to the theory that the Islamic State is underreporting its claims and that the group has remained more resilient than its attack claims suggest, even though three of its highest leaders have been killed in the past year and a half.

Moreover, when combined with the revelations from the leaked internal Islamic State documents, it would suggest that if the military officials within the Islamic State decide at any point in the future to be more forthcoming about operations, the perception of the group’s strength could alter quickly.

It is plausible that Islamic State military officials are conducting hybrid information warfare to lull their enemies into believing the group is weaker than it actually is. This campaign of suppression is also likely targeted toward the United States in particular, the key player in the fight against the Islamic State. In recent years, the Islamic State’s messaging has consistently claimed that the United States has been weakened since COVID-19. For example, in the most recent message from the Islamic State’s official spokesperson on August 3, 2023, announcing the newest “caliph,” Abu Hudhayfah al-Ansari stated:

As for crusader America: in the past, God inflicted torture upon you at our hands. Today, He inflicts torture upon you from Himself as a just punishment for your war against God’s loyal followers. By God, to us it is the best torture since we give glory to Him as the lord of honour. It is most healing to our hearts, and most grievous and severe to you. It started with the coronavirus [Covid-19] plague, and then came its economic consequences and crises for you. It does not end with your immersion in the quagmire of a crusader-crusader war, which exhausted your economy and military materials. Worry, unease, and fear is even apparent in the statements of your military officials due to the near depletion of your military arsenal designated for proxy wars. You are now experiencing your dying days and consecutive misfortunes. Praise and thanks be to God. We lie in wait for you with more, God willing.34

Therefore, it appears that the Islamic State is waiting for the United States to lose interest in the region, biding its time for the right moment to come back when the context is more favorable to it. This is even more plausible if the United States were to decide to withdraw forces from northeastern Syria if there is a new American president in January 2025, given former President Trump’s never-followed-through wishes to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria.35

Overall, the Global Coalition Against the Islamic State has rightly sought to highlight successful operations against the group, and the reported numbers from both the Islamic State itself and the RIC both suggest these operations have degraded the group. However, because the group appears to have held back on reporting attacks, it may not be as weak as appears. With this important context established, this article now explores the Islamic State’s shadow governance efforts since 2019.

Shadow Governance Efforts

Only focusing on the Islamic State’s claims of responsibility or propaganda may distort the picture of the group’s strength or seemingly lack thereof. A true picture of the threat posed by the group also needs to take account of the Islamic State’s on-the-ground governance efforts, however intermittent and unsophisticated compared to the heyday of its caliphate. The authors divide these efforts into four parts: taxes, moral policing, administrative documents, and retaking of territory (albeit briefly).

Taxes

One way the Islamic State has attempted to maintain influence in eastern Syria is through the kulfa sultaniyah (royal cost)36 tax whereby it targets oil merchants, landowners, farmers, business owners, shop keepers, doctors, millers, bakers, fuel traders, pharmacists, money exchangers, sheep breeders, and herders.37 The Islamic State reportedly charges 2.5 percent on the value of individuals’ savings and goods.38 The group calls it the kulfa sultaniyah tax instead of the traditional zakat tax because it does not have tamkin over the territory and can only implement the zakat once it formally does so. The Islamic State is able to target potential taxpayers through a network of informants that “monitor sales locations, document quantities sold, and identify recipients.”39

This taxation has several implications. First, the Islamic State uses it as an attempt to demonstrate it still has some semblance of influence in eastern Syria. The ability to collect taxes shows that its authority and influence is not all lost. Second, the group uses this as a mechanism to strike fear into local populations, even going so far as to threaten individuals via WhatsApp to extort such payments.40 The Islamic State has also been known to blow up locals’ stores, houses, or cars if individuals do not pay these taxes.41 For instance, in mid-October 2022, the group blew up a money exchange and money transfer shop called Maktab al-Iman in the town of al-Izbah, due to the owner not paying the tax.42

The aforementioned WhatsApp extortion messages reportedly come from unknown numbers and one-day-used SIMs with alleged receipts bearing the Islamic State official seal.43 These types of activities have been reported across eastern Syria in al-Hawajiz, Diban, al-Rughayb, al-Busayrah, al-Izbah, Hatlah, Khasham, al-Tabiyah, and al-Suwar.44 However, these activities have likely occurred elsewhere as well.

In the latter half of 2021, Islamic State fighters stormed a number of oil fields (in Subaihan,45 Kharata,46 Abu Habba,47 al-Taym,48 and Daas49), demanding a cut of the oil revenue and threatening to kill investors if they were not paid. When an individual does decide to pay the tax, the Islamic State then provides an official administrative receipt for the exchange to show proof that it has been paid (like it did at the height of its governance) so that no other Islamic State members continue to bother them about further payments.50 This provides yet another layer to the Islamic State’s attempts to legitimize itself as being the true power broker locally.

Beyond helping finance the Islamic State’s continued operations, locals have noted that Islamic State fighters making threats have also stated that the funds would go to the women and children held in IDP camps such as Al-Hol, as well as supporting the families of killed Islamic State fighters.51

Moral Policing

Another key component in the Islamic State’s governance infrastructure has been its hisbah (moral policing) patrols. With patrols regulating both men and women, the Islamic State utilized the hisbah to implement its gendered system of control in the territories it administered.52 To showcase that it has continued to administer such justice since 2019, the Islamic State has, for instance, raided shops in villages like Gharibah al-Sharqiya and confiscated cigarette packs and then burnt them in front of onlookers in the center of the village. The group has also blown up schools in places such as al-Hawajiz for supposedly teaching what the group deems an un-Islamic education.53 Similarly, in September 2020, four Islamic State members paraded through al-Busayrah while chanting “dawlat al-islamiyah baqiyah” (the Islamic State remains), and destroyed a shop selling hookahs, as smoking shisha is against the group’s interpretations of Islam.54

In late June 2021, there were reports of a number of incidents in the eastern Deir ez-Zor countryside of the Islamic State’s hisbah apparatus harassing and warning different segments of the population to stop conducting certain activities that violate the group’s morality laws.55 Islamic State members stopped a taxi transporting women to work on farmland and demanded that they not wear makeup.56 These same Islamic State-affiliated individuals also called on all public transportation operators not to transport women contravening the group’s approved dress code.57 The Islamic State also threatened restaurant and cafe owners for playing live and recorded music.58 In late May 2023, Islamic State members posted leaflets on walls in mosques and public places in the town of al-Shuhayl that ordered women to commit to the group’s version of modesty, including wearing the niqab or face punishment.59 Similar leaflets were found in al-Tayana in early August 2023 as well.60 These calls harkened back to the peak of the Islamic State caliphate.61

Beyond warnings, the Islamic State hisbah killed an individual the group claimed was practicing sorcery and other individuals supposedly selling drugs.62 The Islamic State hisbah also burned a liquor store and confiscated large quantities of tobacco.63 This makes it clear that although the Islamic State is no longer actively controlling territory, it is seeking to still control the behavior of local populations.

Administrative Documents

Another method the Islamic State has used to showcase its relevance and endurance is by continuing to post administrative documents (official governmental documents versus propaganda) from its Wilayat al-Khayr and Wilayat al-Barakah and then subsequently from its Wilayat al-Sham (Syria Province) office. For example, in October 2019, the Islamic State printed a statement directed at those working in the education sector for the AANES, warning them not to work with this “atheistic” system.64 The group stated that it would attack individuals that did not abide by its order. These threats caused female teachers in particular to continue to comply with the Islamic State’s ‘modesty’ strictures. For example, one 28-year-old female teacher stated that she continued to wear the full-face and body niqab while teaching in a local elementary school because she was afraid to expose her face in front of her students, who were all below the age of nine.65

The Islamic State’s general security official in the region issued additional threats in April 2020 via a hand-written pamphlet that was distributed door-to-door in al-Husseiniyah village, again, warning that anyone who was working with the AANES, or the SDF this time—whether as a combatant, teacher, or council member—was a legitimate target in the Islamic State’s ongoing assassination campaign.66 Furthermore, following the implementation of a new school curriculum by the AANES, the Islamic State released an administrative document under its al-Barakah province again threatening teachers and institutions if they implemented the changes, because the group deemed them un-Islamic.67 The Islamic State sought to utilize and co-opt pockets of local anger against the new curriculum from the general Arab populace, some of whom also saw it as foreign to their more traditional education.

In March 2021, the Islamic State became even more brazen, releasing an administrative document with the names of 27 people from the town of Jadid Akidat who were described as apostates because of their supposed cooperation with the SDF.68 The document threatened that if these individuals did not repent, they would face death and their homes would be destroyed.69 The group also warned that additional names would be added to the list soon, illustrating the scope of the Islamic State’s assassination campaign just in one village.70

Highlighting the influence the Islamic State has continued to hold, according to a February 2022 investigation from The Washington Post, one way the organization has been able to keep track of local residents is through informants it pays off.71 As highlighted above, despite its lack of control of physical territory, the Islamic State has sought to continue to release administrative documents seeking to enforce its writ on the local populace.

Retaking Territory Briefly

Due to strategic restraints, the SDF often withdraws from rural villages when the sun goes down due to high security concerns.72 This limited gap in governance and control has allowed the Islamic State to take advantage of the situation and occupy parts of villages overnight. In doing so, it not only undermines the SDF operations in the area, but shows local populations that not only was it not defeated, but it can still exert power, even if not permanent control.

In addition to its nighttime operations, in late November 2019, Islamic State elements controlled parts of al-Busayrah and Ibrihimah wherein they set up checkpoints and scrutinized individuals passing through against their records of residents in the area from when they were fully in charge.73 According to a Syria Direct source in the Special Protection Division of the Internal Security Forces of the AANES in mid-June 2022, there are direct “instructions from leadership [of the Internal Security Forces] not to travel at night on the highways between cities, especially isolated [ones]” and that there are remote areas “with no security and military checkpoints” whatsoever.74

Since mid-July 2022, there have also been reports from locals in places like Diban and Sweidan that the Islamic State is once again openly recruiting individuals in mosques and squares.75 The group also has spaces to run so-called “repentance” sessions to convince individuals to follow its ideological path. In one instance, the Islamic State promised locals salaries of $150-$200 per month, a personal weapon and motorcycle, and a future guarantee to financially support recruits’ families if they were killed in the line of duty. The paying of these salaries harkens back to the Islamic State’s peak, where it had thousands of individuals on its payroll.76 Through new recruitment efforts, this has allowed the Islamic State in Diban and Hawajiz, for example, to set-up daytime checkpoints between regime and SDF-controlled areas to push its aforementioned kulfa sultaniyah and hisbah agenda upon travelers. According to SDF officials speaking to Voice of America in October 2022, the Islamic State has had more room to operate in the eastern Syria due to SDF “preoccupation with other security threats facing the region,” such as the Turkish-backed campaign of the Syrian National Army (SNA) to fight the SDF.77 This claim, however, lacks credibility given the SNA has been attacking SDF targets for more than a half of a decade.

More recently, in late March 2023, locals began describing the towns of al-Shuhayl, al-Busayrah, and Diban as the “Bermuda Triangle” due to the Islamic State’s sway over the areas.78 Moreover, in another one of the Islamic State leaked documents, it claimed that 70 percent of its fighters were based in these areas.79 Residents have recently been too fearful to let the SDF know about the Islamic State’s positions, because the Islamic State uses its records of locals from the time when it was in territorial control of the area to threaten local populations into compliance. For instance, a resident from Hajin who was picked up by the Islamic State at a checkpoint in Diban was later found beheaded by the group in the town of Sweidan.80 Moreover, in July 2023, members of the Islamic State openly participated in a large caravan demonstration through the town of al-Izbah against the Iraqi Christian individual that had recently burned the Qur’an in Sweden.81

Conclusion

The fight in Syria against the Islamic State continues, though as time goes on, some of the coalition against the group seems to be losing resolve to continue for the long term. With increased normalization with the Assad regime and escalating conflicts in Africa and Europe, there appears to be a growing perception by the political class in North America and Europe, and many in the populace, that there is no reason to remain in Syria. While international events around the world appear to be pulling attention away from the activities of the Islamic State, it is important to remain focused on the group, its insurgency, and its future governance ambitions.

Local events on the ground also appear to highlight an unclear future for the region. Dissatisfaction with the SDF’s governance agenda seems to have hit a breaking point on August 27, 2023, when the SDF arrested Ahmad al-Khubayl (Abu Khawla), the head of the Deir ez-Zor Military Council for alleged “communication and coordination with external entities hostile to the revolution, committing criminal offenses and engaging in drug trafficking, mismanaging of the security situation.”82 The SDF also pointed to “his negative role in increasing the activities of ISIS cells, and exploiting his position for personal and familial interests.”83 Some may see recent events as an opportunity for the Assad regime to take advantage of the unstable situation;84 yet, there is no love lost between many of the tribes and the regime. While it is important to track the ongoing relationship between the AANES and local tribes,85 in the fight against the Islamic State, it is paramount to not lose sight of the group’s ambitions and the possible opportunities for it to take advantage. As the Islamic State itself recently taunted, it sees these events as part of a broader “world order reeling,” which God has arranged to “prepare the land” for creation of a “divine order” whose “nucleus has been established by the [Islamic State] Caliphate.”86

Today, the Islamic State’s insurgency capabilities appear to be declining due to Coalition operations. However, as detailed through the authors’ analysis, these numbers may not be all that they appear, and those focusing on countering the Islamic State should not become over reliant on these statistics.

The various forms of Islamic State shadow governance detailed above highlight that the group appears to have more control than what its official media output reveals. This analysis has painted a more complicated picture of a resilient Islamic State that seeks to take advantage of any crack in the foundation of AANES governance or any lull in the SDF and coalition’s counterterrorism operations.

This resilience by the Islamic State means that if the campaign against the group loosens—either because of another tribal uprising,87 the SDF being more focused on Turkey, the United States withdrawing from Syria, or the Assad regime and its allies taking over the area—the group could resurge quickly. The Islamic State has learned from its past governance and has laid the foundation for a future administration. Even if it sounds far-fetched now, a reasonable worst-case scenario is that the Islamic State could rapidly take advantage of a changed local context to attempt to carve out a small statelet in eastern Syria again.