The naked & the dead

Amid an eerie calm, war-torn Syria stands exposed to strange new perils

Original article by Lakshmi Subramanian, The Week, January 11, 2020

Amani Fathima was 28 when she took the vacation that ruined her life.

In late 2014, she and her husband, Hussaifa, and their three-year-old son Kisar, left her in-laws’ home in Mumbai for Bahrain. It was to be the start of an exciting tour of the Middle East—a break from their dull, middle-class life in Kurla West. At least, that is what her husband had told her.Life in Al-Hol becomes hell during the rains. Water seeps through the tents and sewers overflow, turning the camp into a den of diseases.Baghdadi has a lot of blood on his hands. There was a lot of oppression happening, and a lot of injustice, too. – Shahan Chaudry, an inmate of the Al-Hasakah prison[The brigade members in AL-HOL] are extremists. They tell me that I should follow the Quran and shariah. – Geeta Raj, an inmate of the Al-Hol campRussian prisoners in AL-HOL are the most extreme. They dominate the four brigades, each of which have a specific function.

Their host in Bahrain was a friend of Hussaifa, a man Fathima referred to as ‘bhai’. The family spent three months in the country, before they packed their bags for Turkey.

In Istanbul, they checked into a hotel room. Fathima remembers being over the moon. She was pregnant with their second child, and spent most of her time in the hotel room. Hussaifa would go out often to meet his friends.

After spending five days in Istanbul, they headed south to the Turkey-Syria border. It was 2015, and things had taken a dark turn in the region. An extremist group called Islamic State had captured swathes of territory in Syria and neighbouring Iraq, and declared itself a caliphate. Its reach extended from Mosul in Iraq in the east, to the outskirts of Aleppo in Syria, 600km to the west.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the Iraq-born IS chief, had called upon all Muslims to join his caliphate. Hussaifa wanted to answer that call. He took Fathima and Kisar to the northern periphery of IS-held territory—a small town called Tell Abyad, close to the Turkey-Syria border. “I did not know where my husband was taking me,” Fathima told THE WEEK. “I did not have any option but to follow him. I still believe that he, too, did not know what lay next for us. We were following bhai’s instructions over the phone.”

Tell Abyad, which was part of Syria’s Raqqa province, had fallen in 2014. IS had plundered the town and driven away its diverse population of Syrians, Kurds, Arabs and Assyrians.

Hussaifa, however, was hopeful of finding a job, and he promised Fathima a peaceful life—just like the one they had in Mumbai. Their daughter Yahya was soon born.

Hussaifa’s plans fell through in May 2015, when Syrian and Kurd forces launched an offensive to free Tell Abyad. As the battle raged, the family was forced to move deep into IS territory. Fathima was pregnant again, and Hussaifa took her 100km south to Raqqa, a historic Syrian city and the de facto capital of the caliphate. He took up a job there, and their third child, Aisha, was born.

Two years later, mayhem broke out again. Under siege from a coalition of international forces, IS had withdrawn from many of its strongholds in Syria and Iraq. By 2017, its territory had shrunken significantly. Mosul had been freed and Raqqa was the only major city under IS occupation. In October that year, the coalition forces began their final attack on Raqqa.

According to Fathima, Hussaifa died when a shell hit him in 2018. “My husband was not a fighter. He did not go to the battlefield to fight for IS. But I do not know what his job was,” she said.

As IS began losing Raqqa, Fathima and women like her fled to Baghouz, a Syrian town near the Iraq border, around 250km southeast of Raqqa. In March 2019, Baghouz became the last IS stronghold to fall. “I surrendered to the Kurdish forces,” she said. “There were many young women from India [in Baghouz] when I surrendered. But I do not know where they are now.”

Fathima, now 33, and her three children are now at a sprawling refugee camp at Al-Hol in eastern Syria. The camp houses more than one lakh people from nearly 50 countries, including widows and children of IS fighters. The facility is more like a prison; families live in seemingly endless rows of tiny tents that have muddy floors covered by thick sheets.

Life in Al-Hol becomes hell during the rains. Water seeps through the tents and sewers overflow, turning the camp into a den of diseases. There are four hospitals inside the compound, run by around 30 aid groups, but demand always outstrips supply. “Please take me back home,” said Fathima. “Life is very difficult here. It is cold, and the children often fall sick.”

Deputy Photo Editor Bhanu Prakash Chandra and I visited Al-Hol on a soggy December afternoon. Fathima and her daughters sat with us in the camp office. Kisar, who had turned eight, was guarding the tent.

We sat in one of the two makeshift rooms that were fenced off from the main office space. The rooms had thick walls and PVC doors. One room was exclusively used by officers of the Syrian Democratic Forces, a coalition of Kurdish, Syrian and Arab militias that run the camp. The other room served as a lounge for visiting diplomats, journalists and researchers. There were brown sofas all around, and a small glass-topped table holding an ashtray.

We had entered the camp at noon after rigorous security checks. A young Kurdish officer called Aveen had received us in the office and served us hot black tea. She talked about the difficulties in running the camp, before asking us who we wanted to meet. “I want to look for Indians,” I said.

She then arranged for armed guards to escort us to the annex, a section where 12,000 wives, widows and children of IS fighters are held. Before she took leave, she told me: “Wrap your shawl around your head. The women inside are highly religious, and they might attack you if you do not.”

The annex was a place of tension and commotion. There were women shouting at the guards in strange tongues, babies crying nonstop, and mothers calling out for help. The nervous guards kept a tight grip on their rifles, fearing that they would be attacked any time. It was in this cauldron of resentment that we found Fathima.

Clad in a burqa, she was holding her daughters with both hands. When she was told that we were journalists from India, she cried and begged us to help her return home. “Mein aapko kya bulaoon—didi ya behan? Mujhe yehaan se leke jayiye (What should I call you, sister? Please take me with you when you leave),” she said.

The camp authorities allowed Fathima to spend 15 minutes with us in the visitors’ room. She came with a friend—a woman from Seychelles who knew Hindi. As Fathima recounted her tragic tale, the woman interrupted her several times, asking her not to reveal certain details. I asked the Seychellois woman, who was also clad in a burqa and had her daughter on her lap, how she knew Hindi. “I learnt it by watching Bollywood movies, before I came to Syria,” she said.

I asked Fathima about her relatives. She said she hailed from Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh; Hussaifa was her cousin. “It was only after reaching here that I knew we were in a different land,” she said. “I managed to reach my family over phone and inform them that I do not know where I am, or where I would be taken.”

Fathima began to talk about life in Azamgarh, and then stopped abruptly. “I have a brother. He was talking to me earlier. No, I don’t want to reveal who he is,” she said.

Her only prayer, she said, was to return home. Diplomats and activists from other countries had been visiting Al-Hol regularly to look for their nationals. We were her great hope, said Fathima, as this was the first time that Indians had come calling. “I don’t talk to anyone here, except one or two families,” she said. “The others are dangerous extremists. I could get killed if I oppose them. So I stay away from them and take care of my children.”

She hugged me before she took leave. “I want to leave this horrible place,” she told us. “Please help me.”

Land of oil and terror

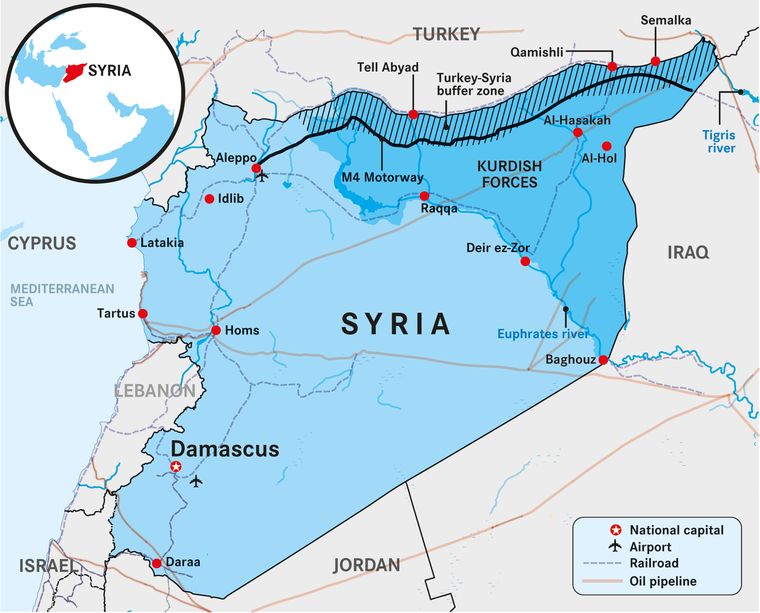

The map of Syria resembles a stocky bird taking flight—its head and beak pointing northeast, to the tri-junction of Syria, Iraq and Turkey. The bird’s head is marked out by the river Euphrates, which enters Syria from Turkey a hundred kilometres west of Tell Abyad and drains out southeast to Iraq and the Persian Gulf.

The Euphrates is a natural barrier that divides northeastern Syria from the rest of the country. Its basin is so fertile that it was where humans first started agriculture, more than 9,000 years ago, and where civilisation first took flight.

Like any bird, pre-war Syria, too, depended on its head and beak for sustenance. It was from the northeast that the country drew much of its oil and agricultural wealth. In 2008, long before the IS rampage began, Syria used to produce more than 4,00,000 barrels of oil a day, mainly from the wells in the northeast. By 2018, the output had plunged to just 24,000 barrels.

Even though IS has been defeated, Syria cannot hope for an immediate turnaround in its fortunes, because the northeast has become an autonomous region under the control of the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces. The SDF, which has its quarrels with the Bashar al-Assad government in Damascus, calls the region Rojava. It exists as a federated union of nearly a dozen autonomous subregions. Rojava’s most populous city, Qamishli, serves as its de facto capital.

Qamishli does not have a fully functional airport. So, to enter Rojava, we touched down at Erbil in Kurdish-held Iraq, and travelled 200km northwest to the Semalka border crossing, manned by the SDF. A pontoon bridge across the River Tigris took us from Iraq to Rojava.

Qamishli lay another 100km away. The road to the city was narrow and ridden with potholes, and it stretched across a barren landscape dotted with huge, rusted, crane-like structures. These were pumpjacks, which help draw oil from onshore wells. The pumpjacks were going up and down nonstop, as red pillars of fire and huge black clouds rose above the horizon. The refineries were being fed, apparently.

As we neared Qamishli, we saw oil tankers lining the road. Further ahead, at a village called Gire Kire, a series of tanks and open pits stretched along a dirt-filled road. These tanks and pits serve as stopgap refineries. Crude is burnt in open pits, producing limited yields of poor-quality petroleum products that are piped into tanks for filtering.

The technique is primitive, and it causes huge environmental damage. It had left the earth in Gire Kire inky black. Streams of leaked oil and layers of slippery sludge made it difficult for workers to even walk.

As we watched, a short man with a red-and-white scarf tied around his grimy face came to us. Yakub Ali, 38, said he used to be a wheat farmer. The war left him working in the refineries. “I lost my farmland in the IS attack three years ago,” he said. “But life has to go on. I have five children. What else can I do to feed the family?”

IS began taking control of the oil fields in Rojava in 2012. Oil production and smuggling became its major source of revenue after it seized the wells in Deir ez-Zor province in southern Rojava. In October 2015, production and smuggling hit a peak of 40,000 barrels a day, helping IS earn around $40 million a month.

The SDF took back control of the wells in 2017. Since then, Rojava has been deriving its political leverage from oil. “We control at least 70 per cent of the oil resources in Syria,” said an SDF officer. “It is our main source of revenue.”

Rojava is now largely a safe zone, but geopolitics deny it lasting peace. Last October, Turkey launched a cross-border offensive against the SDF to create a 32km-deep buffer zone along the Syrian side of the border. Turkey is trying to use this buffer zone to resettle Syrian refugees who had crossed into the country in recent years.

Turkey’s actions are prompted by the US withdrawal from Syria. Turkey views Kurdish fighters as terrorists, even though they had helped US troops in Syria kill Baghdadi in October. The Kurds view the US withdrawal as a betrayal, one that could force them to cut a deal with the Syrian government, with Russia acting as the go-between. Rojava believes it holds a trump card in this great game—the oil fields.

As things stand, the situation remains volatile. Qamishli is very close to the border, so it is part of the unstable buffer zone that Turkey has created. The city had come under heavy fire during the Turkish offensive in October, but things have calmed down now. Qamishli is now largely considered safe, despite stray incidents of violence.

From Qamishli, we travelled south to Al-Hasakah. The shortest route to this major city is an 85km-long desert highway that remains vulnerable to attacks by IS sleeper cells. So we took the roundabout route, travelling 125km through the M4 Motorway, which is perhaps the most important highway in Rojava now. (Before the Turkish offensive last October, the M4 connected Qamishli to the eastern tip of Rojava—a Kurd-dominated town called Kobani. Realising that controlling the M4 meant cutting the Kurd forces into two, Turkey quickly moved into eastern Rojava. Kurdish fighters were forced to push back, helping Turkey establish the buffer zone. Today, because it runs roughly parallel to the international border, the M4 serves as the de facto boundary of the buffer zone on the Syrian side.)

The wheat fields that once flanked the M4 are now barren. We took the exit to Al-Hasakah, which leads to the towering stone walls of the city’s huge, high-security prison. There was an eerie silence as the prison gates opened. And it remained unbroken as we walked a pebbled pathway inside the compound that held more than 7,000 IS fighters awaiting trial.

The prison director was waiting for us outside another huge iron gate. Clad in combat fatigues, and with a trench coat slung over one shoulder, he shook hands with us, but did not reveal his name.

The armed guards who took over from him asked us to be cautious while talking to prisoners. Do not let slip any news or information, they said. “You are forbidden from talking about the Turkish attack in the northeast,” said one guard. “Or about the Americans withdrawing from here, or about Baghdadi’s death.”

With that warning, we were allowed to walk in.

Terror in quarantine

The prison cells in Al-Hasakah have thick steel doors painted green. The doors have apertures big enough for prisoners to stick their heads out, but they mostly remain covered by metal plates. As an armed guard opened one aperture, a hollow-eyed man poked his head through. He said his name was Isha Hamad Hussain, and that he was Syrian.

I told him that I was a journalist from India. “Do you know Kerala? Are you from Kerala?” asked Isha. He had pale skin and dark circles around his eyes; he said he had not seen sunlight for months. “I was not a fighter,” he said. “But they brought me here, after they arrested everyone in Baghouz.”

As Isha drew his head back, I looked into the cell. At least a hundred men in orange jumpsuits were crammed into the room. Most of them were as hollow-eyed and skinny as Isha was, and many of them had shaven heads and broken limbs. A few ate from plastic cups and plates, while some others lay on the floor motionless. A black plastic sheet covered a small enclosure at the far end of the cell—providing privacy for the inmates, but there is no escape from the stench in the air.

The opening in the door suddenly slammed shut from the inside. I moved to the next door. Two men peered out as the guard slipped the latch. Rashid, a 21-year-old former fighter, believes that IS continues to survive. “What if Baghdadi dies?” I asked Rashid. “IS will continue to exist,” he replied.

The other inmate, a 17-year-old, asked me about the news. The light inside the cell suddenly went out and both the prisoners withdrew into the darkness.

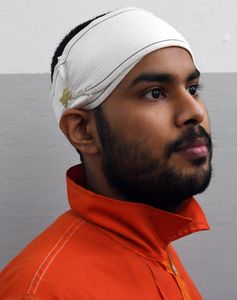

I told the guard that I wanted to look for prisoners from India. He produced a thin, frail man in a dirty jumpsuit, with a bandage tied around his forehead—Shahan Chaudry, 32.

A native of Punjab in Pakistan, Chaudry had been studying gaming design in London and working part-time at a post office when the war in Syria broke out. He went to Syria in 2014. “The Syrians were being bombed, and no country was coming to their aid,” he said. “I was just 27 and I decided to come and help. I came in through Turkey and then reached Idlib [in Syria]. I worked for an aid organisation—distributing food, clothes and medicine in the upper provinces.”

As IS began to gather strength, Chaudry got attracted to its extremist ideology. A group of injured IS fighters who had come to Idlib for treatment took him to IS territory. “The road was open at that time,” he said. “And so I came into the caliphate with them. I first went to Novan in Aleppo province.”

He underwent the standard training for outsiders—military exercises and a course in shariah, the Islamic law based on the Quran. “They send you to work,” said Chaudry. “I was sent to a checkpoint. I underwent a month-long military course and learnt to operate automatic rifles.”

His initial days were mostly peaceful, so he arranged for his wife and daughter to come to Aleppo. “She was very happy in the caliphate,” he said. “No one would make fun of her for wearing the hijab. We were happy that we could perform prayers five times a day.”

Chaudry and his wife had four more children while they were in IS territory; one child was killed in the final stage of the Kurdish offensive. The family surrendered in Baghouz; he was taken to Al-Hasakah, while his wife and children were sent to Al-Hol.

He has no regrets about the choices he made; the overwhelming feeling, he said, was of fatigue. “Most people here are like me; they are tired,” said Chaudry. “I have never been in one place for the past five years. I kept moving and moving. Had I known that I would end up in a place like this, I would not have surrendered in Baghouz. I would have waited for a rocket to hit me between my eyes.”

But Chaudry fears for his wife and four children. “Are you going to Al-Hol?” he asked. “My children were very weak when we surrendered. Can you help me reach them?”

I said I would try, and asked about the details. But he clammed up soon after he began talking about his family and parents in Pakistan. “Don’t go into specifics,” he said.

That his story was riddled with lies and half-truths was clear, just like his abiding love for the IS way of life. “I don’t want [Baghdadi’s] IS to exist,” he said. “I want Islam to exist. [I am for the] Islamic State that existed in the days of Prophet Muhammad. We understand that Islamic State from a theoretical point of view—a state that existed way before IS, during the days of Prophet Muhammad. Those were the righteous people.”

As he talked about the error of Baghdadi’s ways, he abruptly paused. “Do you have a chocolate? Can you get me a chocolate? It has been nine months since I have had a chocolate,” he said.

I arranged for a bunch of chocolate bars. “Are all these chocolates for me? I can eat them as we talk?” he asked in disbelief. He ate them as he talked about why Baghdadi’s IS fell.

According to Chaudry, Baghdadi started off well by establishing a functioning state with its own public utilities, welfare systems and health care services. “Anything that is a non-democracy or is alien to the western culture, people see it as abnormal. They look at it as a threat,” he said. “IS’s foreign policy was to retake those lands that once belonged to Muslims, and to bring them under Muslim rule. So, when you see IS from a western perspective, you see it as a threat—which is why the world called it a terrorist organisation. But, in terms of governance, IS was a fully functioning state, just like India, England or any other country.”

Chaudry was not entirely wrong. At its peak, IS controlled a third of Syria and nearly half of Iraq—an area roughly the size of Uttar Pradesh—and ruled over more than one crore people. Its fledgling economy was powered by oil revenues, donations from abroad, illicit taxation, slave trade, sale of antiquities, ransom and extortion. In 2015, the Financial Action Task Force reported that “IS had focused on bank looting activities in Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city and a major financial centre, and had reportedly installed managers at many bank branches there [to levy tax on customer cash withdrawals]”. IS ran more than 20 banks in Syria alone, said the report.

So what went wrong, I asked Chaudry. “The Iraqis took over,” he said. Apparently, Baghdadi was partial to his countrymen. “There were Iraqis in every top position in IS,” said Chaudry. “They were related to each other. This was the beginning of the fall.”

According to him, the IS bureaucracy slowly turned corrupt because of nepotism. The Iraqis began suspecting foreigners who had migrated to the caliphate, accusing them of working as informers for governments abroad. “They ended up killing a lot of foreigners like me,” he said. “A few of my friends were killed, without any inquiry or evidence.”

Chaudry was unaware that Baghdadi had been killed, or that IS was no longer a geographical entity. “Baghdadi has a lot of blood on his hands,” he said. “There was a lot of oppression happening, and a lot of injustice, too. For example, the rations would go to only those people close to him and not to the children. The children were malnourished. I cannot get into specifics, but I know he made a lot of mistakes.”

With IS gone, it may be the Kurds who may end up paying for Baghdadi’s mistakes. Most of the prisoners languishing in Al-Hasakah are still indoctrinated, posing a grave threat to the Kurdish militia that runs the prison. Their strength was reduced after fighters had to move to the border to stop the Turkish offensive. The Kurds now worry that the inmates may trigger a mutiny and escape. Also, hundreds of prisoners—mainly those who came to Syria from the west—have been stripped of citizenship by governments abroad.

It means men like Chaudry cannot return to normal lives, nor can the Kurdish hope to expatriate them.

Killer ladies and lady-killers

When THE WEEK met Sterek Judhi, she was dressed to kill.

The 19-year-old Kurdish fighter was in a khaki jumpsuit, with a bandolier and a Kalashnikov. She looked pale and frail, and did not look the part of someone who had fought on the front lines against IS, killing at least six men and injuring scores of others.

“For an IS militant, the worst thing that could happen is to get himself killed in the battlefield by a woman,” she said. “They believe they would directly go to hell if that happens. I am a very happy woman; I have sent a few men to hell.”

Sterek, whose name means ‘star’ in Kurdish, is a rising star of the all-female branch of the Kurdish militia. The branch comprises around 10,000 fighters aged between 18 and 25, and they had fought alongside the male units of the SDF to defeat IS and secure Rojava.

Sterek hails from Derik, a small town in southern Rojava. She joined the Kurdish military school as a 13-year-old, ignoring strong opposition from her family. At the school, she spent five years undergoing basic training and studying political theory. “We are given full-fledged military training only after we turn 18,” she said.

A crucial part of the training is psychological. At Kurdish community centres in Syria, women are taught how to defend themselves, recover from battleground blows and be independent. “These centres help us understand that we need not accept everything in a patriarchal society,” she said.

The Kurds are the largest ethnic minority in Syria, making up nearly 10 per cent of the population. There are nearly 3.5 crore Kurds worldwide, most of them living in the historical Kurdistan region that is split up between Syria, Iraq, Iran and Turkey. The Kurdish are a largely conservative community, but the women are more progressive than those in other ethnic groups. “I want to be independent,” said Sterek. “I am happy being here in Qamishli. I make close to $200 a month, which is more than enough.”

Around 90 kilometres south of Qamishli lies the Al-Hol camp, where we met women who were the antithesis of Sterek. Aveen, the women Kurdish officer who received us in Al-Hol, had warned us that the women prisoners in the camp were highly dangerous. Just how dangerous they were, we knew only after walking through the annex, the area reserved for IS widows and wives.

The annex is a mini caliphate. Ultra-conservative inmates have formed four brigades to enforce shariah. Those who violate the Islamic law are given swift and often violent punishments. “Women are barred from coming out of their tents without a hijab,” said Geeta Raj, a 31-year-old from Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka. “[The brigade members] are extremists. They tell me that I should pray five times a day, and follow the Quran and shariah.”

Geeta was a passport officer at the Sri Lankan embassy in Lebanon. Her husband was a Turkish national who migrated to Syria and was later killed. She has three sons, who are now living with her in-laws in Turkey.

Though she is not overtly religious, she is forced to toe the extremist line. Those who do not are often murdered. A few months before our visit, a 14-year-old girl from Azerbaijan rebelled by doing away with the hijab. She was found dead with her neck broken in three places. Autopsy revealed that she was beaten and strangled to death, but the girl’s mother told aid workers that she slipped and broke her neck.

In October, another woman died after being stabbed 16 times. Abdullah Ahmed, a Syrian teenager, was also stabbed to death after being accused of collaborating with Kurdish authorities.

Apparently, Russian prisoners are the most extreme. They dominate the four brigades, each of which have a specific function. The Khansaa brigade is the morality police that enforces the dress code and religious practices, while the Asayish raids the tents in search of weapons and contraband. The third group, Zaid el benat, indoctrinates the inmates and runs the shariah courts. Punishments, including death sentences, are carried out by the fourth group, called the Verdugas or the executioners.

Desperate inmates have tried to escape this mini caliphate by tunnelling their way out of the camp. Al-Hol has rocky soil and the inmates are not allowed to access any equipment, but prison authorities recently discovered that the women had dug several tunnels using the tents as cover. “Some of them managed to escape, but they were later recaptured,” said a guard.

At least 10 escape attempts happen every month. Traffickers charge as much as $15,000 to bribe the guards and help inmates escape. “I tried to escape thrice,” said Adeela Shafiq Yusuf from Pakistan. “Once I tried to jump the fence and run away. But the guards caught me and brought me back. I have got in touch with my family through the NGO Red Crescent. Life is hell inside the camp; I want to be far away from here.”

The camp’s population is booming. More than 600 children were born in the past one year, even though only five of every hundred inmates are male. Girls and boys who grow up in the camp are married off when they enter their teens. To stop the practice, prison authorities have started shifting boys who turn 14 to a separate juvenile home. “Our strength has gone down after the Turkish attack,” said Aveen. “Guarding the camp is becoming a huge task with the available force.”

Walking through the annex, it was hard not to feel a sense of compassion for the inmates. The tents were shabby, the marketplaces were squalid and children were playing in the sludge. But the sympathy vanished when we saw the ultra-conservative women raising their forefingers at us. The raised forefinger is a well-known sign of victory and power, but the IS faithful use it to give a more sinister message. It says they uphold their ideology, which is built on the belief that modernity and all forms of plurality must be destroyed, and that they will work towards fulfilling their mission.

These radical matriarchs of Al-Hol are ensuring that the IS ideology lives on. Their children are so indoctrinated that, whenever outsiders come visiting, they mob them demanding money or gifts, threatening to kill them if they do not oblige. Earlier, near one of the prison hospitals, we had seen a Russian mother flying into a rage as she waited for medicine for her sick baby. She calmed down after a while, but her elder son continued threatening a prison guard. “I will kill you,” he said, repeatedly.

Murky and toxic, Al-Hol is a ticking bomb. As I left the camp, I felt sorry for Fathima, the Indian widow who wanted a better life for her children. But it was another prisoner, whose name I did not know, who had made a lasting impression on me. While at the annex, she had thrown stones at me to make me go away. “We don’t want anyone to come here to tell the world outside about us,” she had said, raising her forefinger. “I follow the Quran, and Allah is our God. Islamic State will live on.”

Names of certain Kurdish personnel have been changed to protect identities.